Ahhhh Beelzebub, the second best demon in hell. Satan’s

right-hand man. The mouth piece of hell. A wondrous foul beast, who is also a

pretty cool-cat. Milton describes Beelzebub as follows:

“Which when Beelzebub perceived—than whom,

Satan except, none higher sat—with grave

Aspect he rose, and in his rising seemed

A pillar of state. Deep on his front engraven

Deliberation sat, and public care;

And princely counsel in his face yet shone,

Majestic, though in ruin. Sage he stood

With Atlantean shoulders, fit to bear

The weight of mightiest monarchies; his look

Drew audience and attention still as night

Or summer's noontide air”

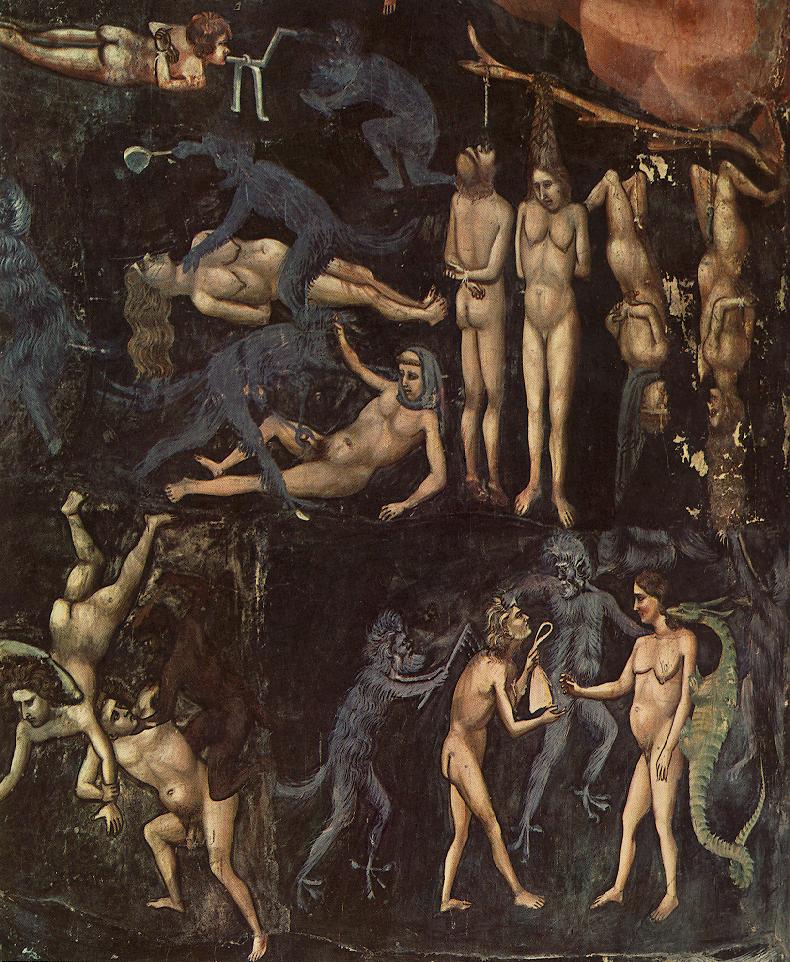

Now, I don’t know about you but I was very excited to see

what the internet was going to find for me—image-wise—regarding Beelzebub. I

hopped for AWESOME, because that’s basically how Milton wants us the readers to

visualize him—a big hulk of monstrous, handsome, conniving, perfection.

Needless to say I was super disappointed in the available

artwork. Apparently there is an anime Beelzebub, but he doesn’t seem very

impressive either. I wonder why he isn’t depicted in art more? I even narrowed

my searches and even looked specifically for Paradise Lost artwork…nothing impressive. For the other demons I

was able to find some pretty interesting artwork, but not for Satan’s

right-hand man, it seems odd... Especially since according to Milton, Beelzebub

was the mouth piece of Satan. I would think he would be seen more, rousing the

other demons to do Satan’s bidding, but somehow making it seem like it was

their idea the whole time. The images I was able to find just left me wanting…